Works from Painting Outside Painting

44th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary Painting

curated by Terrie Sultan

catalog essay on artist by Klaus Ottmann

Corcoran Gallery of Art

Washington, D.C.

1997

44th Biennial Exhibition of Contemporary Painting

curated by Terrie Sultan

catalog essay on artist by Klaus Ottmann

Corcoran Gallery of Art

Washington, D.C.

1997

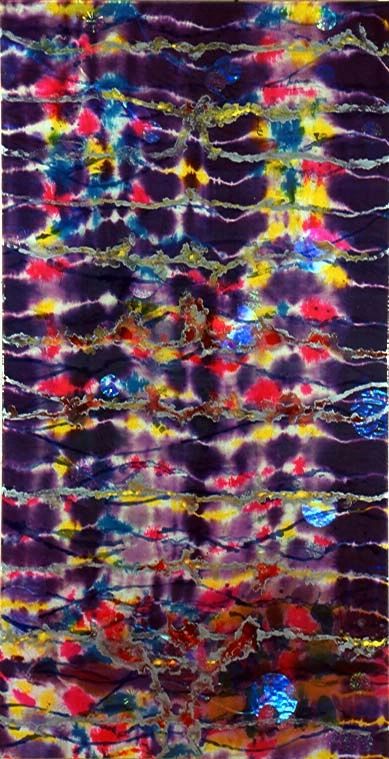

Cover for Catalog

44th annual Corcoran Biennial

Corcoran Gallery of Art

Washington, D.C.

Capital Project: Untitled ( Critical Mess)

Cosmetics, fluids with fabrics and foil over canvas

96" x 72"

1997

Capital Project: Untitled ( Jimi Hendrix )

Cosmetics, fluids with fabrics and foil on canvas

96" x 72"

1997

The Critical Function of Art

Klaus Ottmann

for the catalog of the

44th Corcoran Biennial

Painting Without Paint

The critical function of art, its contribution to the struggle for liberation, resides in the aesthetic form. A work of art is authentic, or done not by virtue of its content (i.e. the “correct” representation of social conditions), nor by its “pure” form, but by the content become form.

- Herbert Marcuse, The Aesthetic Dimension

Peter Hopkins inserts the notion of the beautiful into the (post) modern condition as criticality – as a “critical” quality rather than an appeasing sentiment of taste. Hopkins abandons the text of paintings for a deep and intense visual experience that disrupts the senses by emptying the visual field of his “paintings” of its history and discourse.

Hopkins liberates himself from treating painting as painting by transferring Smithson’s idea of the marked site onto painting. His practice of pouring bleach on canvas and his use of perfume and toxic fluids constitute acts that are both destructive and cleansing; each, in their calculated way, mark a social field and comment on the collapse of painting as model.

Abandoning traditional paint for “social fluids” allows Hopkins to reinvestigate and recontextualize the formal issues of beauty. At the same time, it engages in a political critique which is contained in his material’s reference to issues of the body, sexuality, and the environment.

Applying cosmetic and medical dyes to decorative fabrics and holographic foils, Hopkins creates the façade of a critical sublime that neither excludes the beautiful nor sets itself apart from it. He pushes the sublime further, towards the fringes of social and emotional perception, towards aesthetic entropy.

Just as Smithson brought Cezanne out of the studio again and reclaimed the physicality of his painted terrains, Hopkins reintroduces content into empty formalism by literally spilling the outside of art over into the fabric of his paintings.

Hopkins accomplishes a momentary conciliation of beauty and politics, a synthesis of the sublime and the beautiful that shifts the horror of the sublime for a fleeting Instant to the cathartic power of the purely beautiful – just long enough not to fall into the trap of desire for the fascist terror of unsublimated beauty.

Klaus Ottmann

1995